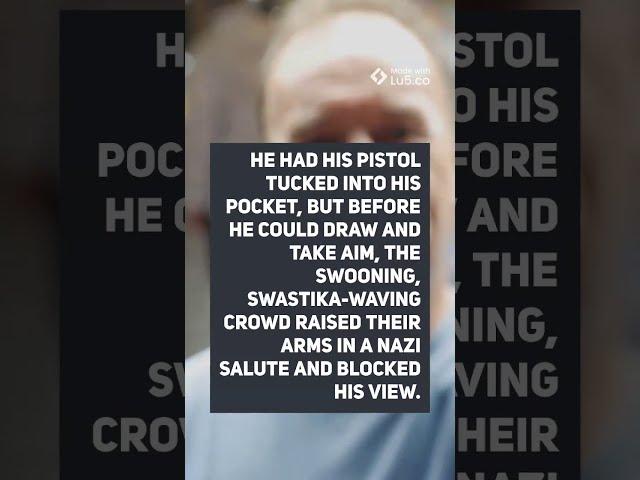

ALL ASSASSINATION ATTEMPT ON ADOLF HITLER PART 1

1943: Rudolf von Gertsdorff’s Suicide Mission Only a week after Tresckow’s brandy bomb failed to explode, he and his co-conspirators made yet another attempt on Hitler’s life. This time, the scene of the assassination was an exhibition of captured Soviet flags and weaponry in Berlin, which the Führer was scheduled to visit for a tour. An officer named Rudolf von Gertsdorff volunteered to be the triggerman for a bomb attack, but after scouting the premises, he came to a grim realization: security was too tight to plant explosives in the room. “At this point it became clear to me that an attack was only possible if I were to carry the explosives about my person,” he later wrote, “and blow myself up as close to Hitler as possible.” Gersdorff decided to proceed, and on March 21, he did his best to stay glued to the Führer’s side as he guided him through the exhibit. The bomb had a short 10-minute fuse, but despite Gersdorff’s attempts to prolong the tour, Hitler slipped out a side door after only a few minutes. The would-be suicide bomber was forced to make a mad dash for the bathroom, where he defused the explosives with only seconds to spare. 6 1944: The July Plot Shortly after the D-Day invasions in the summer of 1944, a clique of disgruntled German officers launched a campaign to assassinate Hitler at his “Wolf’s Lair” command post in Prussia. At the center of the plot was Claus von Stauffenberg, a dashing colonel who had lost an eye and one of his hands during combat in North Africa. He and his co-conspirators—who included Tresckow, Friedrich Olbricht and Ludwig Beck—planned to kill the Führer with a hidden bomb and then use the German Reserve Army to topple the Nazi high command. If their coup was successful, the rebels would then immediately seek a negotiated peace with the Allies. Stauffenberg put the plan into action on July 20, 1944, after he and several other Nazi officials were called to a conference with Hitler at the Wolf’s Lair. He arrived carrying a briefcase stuffed with plastic explosives connected to an acid fuse. After placing his case as close to Hitler as possible, Stauffenberg left the room under the pretense of making a phone call. His bomb detonated only minutes later, blowing apart a wooden table and reducing much of the conference room to charred rubble. Four men died, but Hitler escaped with non-life-threatening injuries—an officer had happened to move Stauffenberg’s briefcase behind a thick table leg seconds before the blast. The planned revolt unraveled after news of the Führer’s survival reached the capital. Hitler supposedly boasted that he was “immortal” after the July Plot’s failure, but he became increasingly reclusive in the months that followed and was rarely seen in public before his suicide on April 30, 1945.

Комментарии:

Cancelaran VAWA?

Abogada de Inmigracion - Yohana Saucedo

The EASIEST 3 Day Fruit and Vegetables Detox!

Love, Nilsa

Saira on Why She Left Malaysia, Taxes, Halal Mortgages, Divorce And More…(EP.079)

Side by Side Podcast with Kazi Shafiqur Rahman

DRAWING YOUTUBERS

TheBrianMaps

5 Cheapest Places to Live in British Columbia with the Best Quality of Life in 2024

Discover Global Living

哪吒是中國人嗎?哪吒的真實面目,印度人、埃及人還是中東人?20250303

Gavinchiu趙氏讀書生活

![How to Connect AirPods to Samsung Smart TV! [Pair] How to Connect AirPods to Samsung Smart TV! [Pair]](https://rtube.cc/img/upload/czd3clJnZURoek0.jpg)